Contaminated blood – lessons for our future

The haemophilia community had long lived with the knowledge that some of the blood products on which they relied for replacement clotting factors were a source of infection with hepatitis A, hepatitis B and non-A non-B hepatitis – later known as hepatitis C. But the arrival of HIV was a blow from which many did not recover.

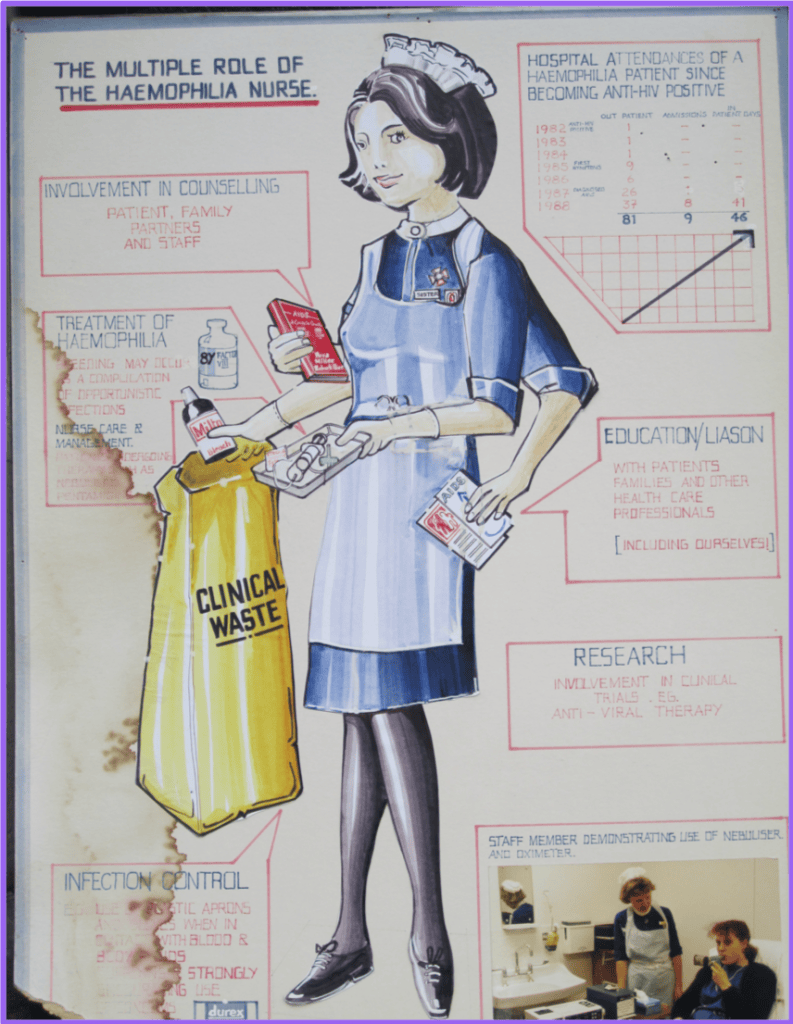

Nurses felt guilty that, having helped families transform their lives with home treatment, they had unwittingly opened the door to this new and frightening risk. “…when we got our tests back in our centre, it was total, absolute shock to find that 90% of our patients were positive and that five of the female partners were positive as well.” Maureen recalled. There was a sense of hopelessness but also a determination that HIV would not win.

Maureen’s colleague, Chris Harrington, started work in 1986, at the height of the crisis. She described “quite a lot of fear, quite a lot of denial and quite a lot of a sense of inadequacy” among patients, families and nurses.

Nurses arranged clinics with longer appointments to help patients and families. People reacted differently, Maureen says: some didn’t want their children to know, some were in denial and didn’t want to come back to the centre. Most did return – because they didn’t have anywhere else to go and they were frightened to talk about HIV to anyone else.

A diagnosis of HIV infection affected the patient, their family and the professionals providing their care. This was a time of guilt, secrecy and stigma. Children refused to confide in their parents. Haemophilia centres provided supported to partners. Whole families were affected – Maureen remembered one family in which 17 members with haemophilia were HIV positive. Some families were resilient, others struggled to cope. Many stopped using blood products but were forced to return to treatment by recurrent bleeds and pain. “I can’t even imagine what it must have been like to make that decision, to continue to treat yourself and not really know what you were injecting,” Maureen said.

Hepatitis C would later be another challenge but Chris said it was as if there was a ‘hierarchy of viruses’ at the time: hep C was not associated with the same stigma as HIV and did not seem as threatening. Consequently, there was a delay before the problem was effectively tackled for some people.

Haemophilia nurses were not spared the stigma felt by their patients. No-one wore gloves in those days. Many were worried they had been infected but were afraid to be tested because they would then be unable to get insurance. Colleagues would cross to the other side of the corridor when they saw a nurse approaching with a tray of blood samples. Unknown to her at the time, Maureen’s pub kept a glass only for her to use.

Nurses are still providing care for patients who didn’t expect to survive and to this day they work with families dealing with losses over several generations. But from great challenges comes great good. Chris has witnessed huge courage and resilience. “I think it set the foundations for teamworking in haemophilia and the importance of that core team; of having a psychosocial professional, having the nurse, the physiotherapist and the clinician working together, having MDT meetings, sharing how you were going to manage situations. And I think it formed strong bonds, not just among ourselves as nurses, but within teams.” The risks of exposure to contaminated blood drove improvements in clinical practice and the product safety, first with high purity concentrates then recombinant factors. The paternalistic culture of clinical practice in the 1980s has changed to one of openness and transparency.

But preparing for this presentation brought back memories that Chris and Maureen hadn’t wanted to revisit.

“Part of you would like to leave it alone, but it’s very much part of the long-term experience. But it’s painful,” said Chris. “I think, on reflection now, I can see that although we were very busy, looking back on it I can see that we needed more time – or I needed more time – to really reflect and process what was happening.”

“Those things never go away, and I’m sure that you’re going to be dealing with the consequences of all of that,” Maureen said. “It reminded me – I was looking in a box – when I retired there were lots of letters and cards and things, and I opened the box and started reading some of these letters, and I just sat in tears at some of the things that were said. It’s still raw. It’s wonderful, but it’s still raw. But we were fortunate to be there – I’m always glad that I decided to be a haemophilia nurse.”