A diagnosis of severe haemophilia means my son gets treatment — Debbie’s story (Part 1)

In the first of a two-part blog, Debbie shares her experience of her son, Jamie, having an unexpected diagnosis of severe haemophilia A.

When Debbie (a pseudonym*) had her fourth child, a diagnosis of severe haemophilia A wasn’t something she and her partner anticipated. Although she worried that something wasn’t quite right when her son Jamie* was born, hospital staff weren’t concerned and put her mind at rest – at least for a while.

“When Jamie was born, both his eyes were full-on bloodshot, but they said it was fine,” says Debbie. “He was my fourth child – he kind of shot out – and they said it wasn’t uncommon with a fast birth.”

Bumps and bruises

Family life over the following months was relatively uneventful, though Debbie notes that Jamie cried a lot. “He was so whingy,” she says. “Every time we got him dressed, moved him, he was always whinging and crying. Now we know that he was probably in a lot of pain.”

As Jamie got a little older, Debbie noticed bruises from minor impacts when he was playing. These disappeared fairly quickly, but when he started to become more mobile, she became concerned. Lumps appeared on his head when he began to roll over, but these were dismissed by her local GP as “just bony prominences”. Then, at eight months old, he began to crawl.

“His knees literally turned black and blue,” says Debbie, “Deep purple bruises.”

Another trip to the GP’s surgery followed. Jamie was seen by a locum doctor who, by chance, recognised the signs of a bleeding disorder. In retrospect, Debbie realises how fortunate this was.

“The GP asked lots of questions and said he was going to refer Jamie for blood tests,” Debbie explains. “He ordered all the tests straight away, the coagulation test – there’s no way he would have ordered that test if he hadn’t suspected haemophilia. He went straight in, knew what to do. That’s quite rare, isn’t it?”

Jamie was diagnosed with moderate haemophilia A and was under the care of a specialist treatment centre within a week.

Care team support

Debbie has nothing but praise for Jamie’s care team and the support and reassurance they gave from the very first time she met them.

“Jamie was eight months old, he was sitting on the floor, and they literally got down to his level,” she says. “They hitched up their skirts and sat on the floor with us, made us feel completely at home, made us feel at ease.”

At this point, Jamie’s moderate diagnosis was changed to severe haemophilia A.

“We looked at each other, me and my partner, and sort of welled up,” says Debbie. “It was even worse than we’d thought, but the nurse said, ‘No, that’s good. Having severe haemophilia means he gets the treatment. That’s a good thing in the long run.’ They put our minds at rest. They gave us a big book of information and from day one said we could ring them whenever we wanted, day or night, any little thing.”

Post-diagnosis feelings

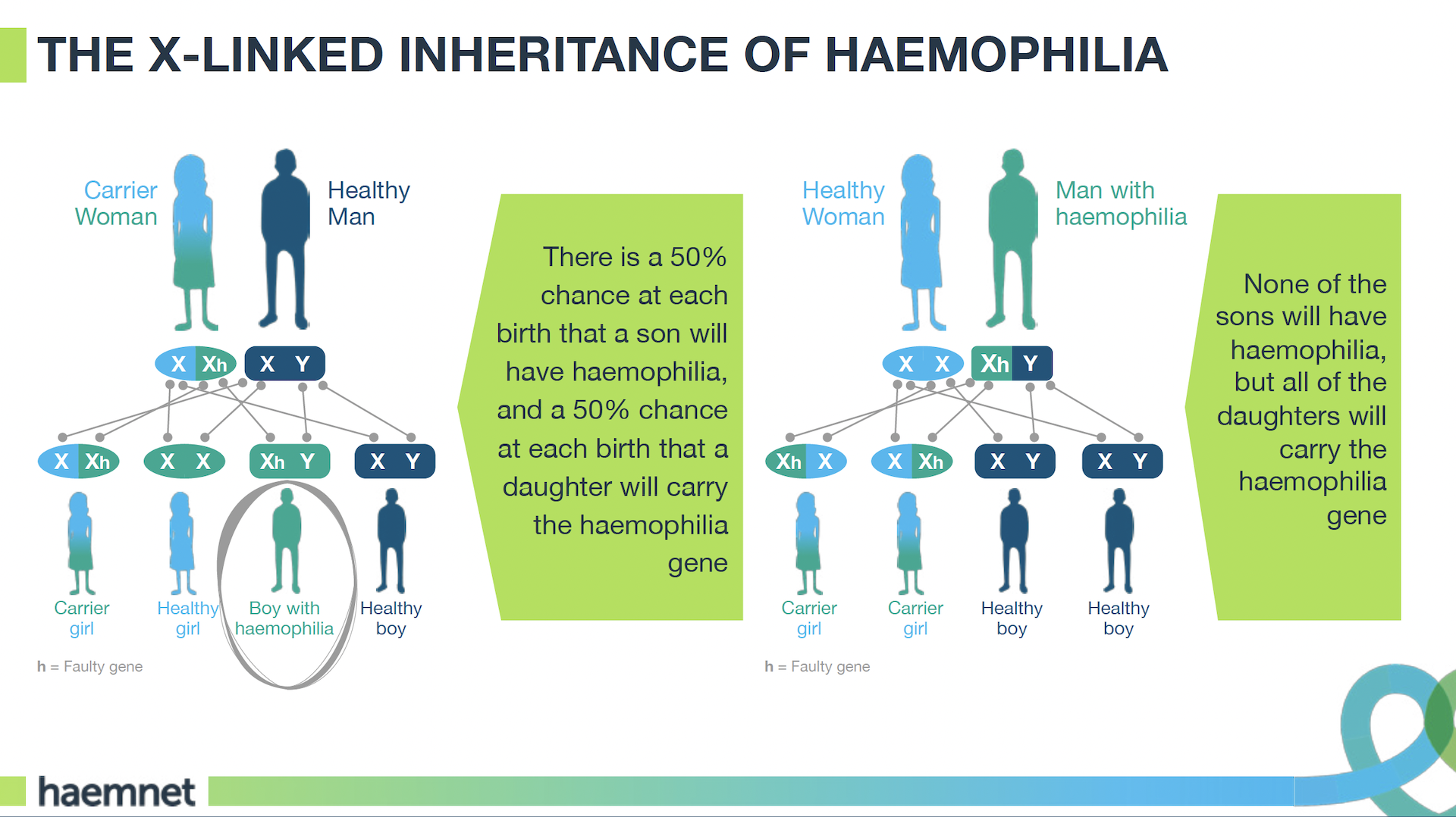

Looking back, Debbie is very matter of fact about this sequence of events. There was no known history of haemophilia in her family, though she was subsequently diagnosed as carrying the haemophilia gene. She has another son and two daughters, one of whom is also a ‘carrier’, and says her family represent the classic haemophilia inheritance diagram.

However, her positive mindset, along with the speed of Jamie’s eventual diagnosis and her confidence in his care team, shouldn’t belie the fact that this was a stressful time for her and her partner. Debbie found the first few months after diagnosis hard. And although she overcame her sense of “mum guilt” quickly, the world seemed a much more dangerous place for Jamie.

“From the beginning, I knew the odds were that Jamie’s haemophilia came from me,” she says. “When he was diagnosed, I cried for a couple of hours, ‘It’s all my fault’, and then it was like, ‘Pull yourself together, get on with it – you’ve got to deal with it now.’

“But I think those first two months were quite overwhelming because the danger just seemed to be everywhere.”

Debbie was advised that Jamie wouldn’t be started on prophylactic treatment until he experienced his first recognised bleed – standard practice in young children diagnosed with haemophilia. But this left her feeling nervous.

“Until Jamie started treatment we felt on edge all the time,” she says. “It was the fact that once he started treatment, he’s got the protection. Until then, he could have a spontaneous bleed, anything could happen. And this is the kid that’s just learning to crawl and walk…”

A&E experience

Jamie was – and still is – very active. Around two months after his diagnosis, Debbie noticed a large lump on the back of his head. She took him to the A&E department at their local hospital but found that staff didn’t seem to understand the potential seriousness of the situation.

“I was a nervous wreck at this point,” says Debbie, “you know, thinking ‘He’s going to have a brain bleed, he’s going to die.’ They were saying, ‘No, it’s fine, it will sort itself out,’ and I’m like, ‘No, he’s got haemophilia, you don’t know the ins and outs of it. I’m not leaving until you speak to someone at his treatment centre.’”

On Debbie’s insistence, A&E staff eventually did get in touch with the treatment centre. With his consultant’s input, it was confirmed that Jamie was fine to go home, but plans for his treatment were put in motion the following day. After having a port-a-cath fitted, he was started on factor VIII prophylaxis at 10 months old. This came as a relief for Debbie and her partner.

“It was horrible when Jamie had his port put in, when he had the operation,” said Debbie, “but we just wanted to take control of the situation. It was going to come sooner or later, and for us, sooner was better, to be in control of our child’s medication, keeping him safe.”

Treatment and taking control

Debbie says that the sense of taking control made learning to treat Jamie much more straightforward. She and her partner worked as a team, making sure they were both able to give treatment. “One would distract and play with him, the other one would do the treatment, and we’d take it in turns so we were both as confident as the other,” she explains. “It was a good thing. Getting the treatment was a good thing.”

This approach to learning to give Jamie treatment stood them in good stead when he had his port removed at four years old and they decided to move to treating him intravenously. Looking at the situation from a practical point of view helped, but Debbie also recognises how important it was to her that she went through the process with her partner.

“You just to just detach yourself from the fact that it was your child and concentrate on the procedure,” she says. “I think if we didn’t have each other, me and my partner, it would have been really hard. But to have each other’s support – and one that could completely focus on Jamie so one could completely focus on the procedure you were doing… We practiced on each other too – we were sticking needles in each other all the time!

“But we took the view that, ‘Right, this is what’s needs doing. Emotion has got to come out of it. The sooner we can do it, the sooner we can protect him.’ Once we had control, that was it. The control of being able to give him treatment took away so much of the worry, it really did.”

With our thanks to Debbie for sharing her story with us.

Read part 2 of Debbie’s story here.

Further information

A number of patient organisations and charities provide support and advocacy for people with bleeding disorders and their families. In the UK these include:

- The Haemophilia Society

- Haemophilia Scotland

- Haemophilia Wales

- Haemophilia Northern Ireland

- Local families with bleeding disorders

Further reading

Debbie’s story is part of a series about the parents of children with bleeding disorders. This also includes stories about the experiences of the parents of two boys with severe haemophilia A, a mother whose daughter has Type 3 von Willebrand disease, and a family with three daughters who have Type 2A Von Willebrand disease.

About the author

Kathryn Jenner is Communications and Community Manager at Haemnet Ltd.