Listen and learn like a legend

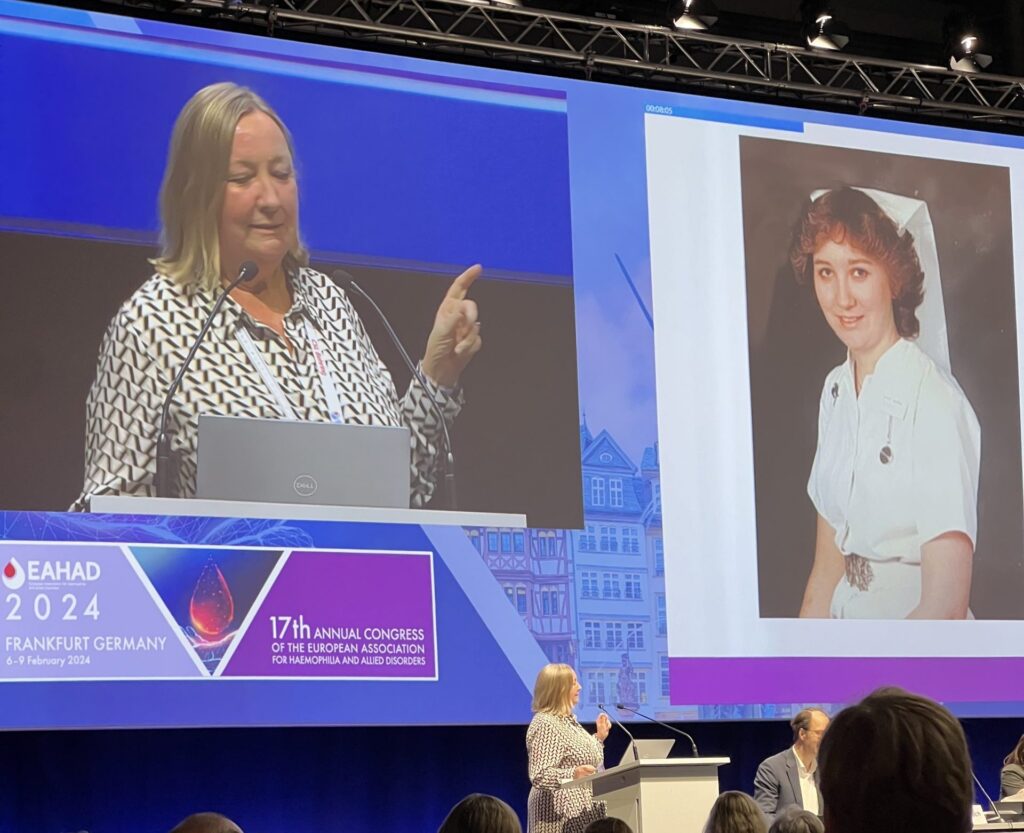

Attending the annual EAHAD congress is always a highlight of the Haemnet year. But this year’s meeting in Frankfurt was doubly memorable. In addition to presenting the results of our latest study (more on that another time), we watched as our very own Dr Kate Khair was honoured by the EAHAD committee for her life’s work in developing the speciality of haemophilia nursing.

As the second allied healthcare professional ever to receive EAHAD’s lifetime achievement award, Kate used her conference speech to reflect on some of the people who had influenced her career in the world of haemophilia.

A nurse since she was 16 years old, Kate started out in oncology but was led astray by a bad boy called Tom (not his real name)! “As well as an untreatable teratoma. Tom also had severe haemophilia. And he knew he would die “and he was so different from all of those other young men that were on that ward.” When she was on nights she would go to the ward and find an empty bed: “He’d gone to the pub. And he was often brought back by the police with a cannula in. And he says, quite honestly, ‘I’ve got this to do my drugs.’”

Tom’s approach to life (and indeed living the best life that he was able to in the circumstances) impacted Kate’s whole way of thinking about living with a long-term condition. She moved to Great Ormond Street Hospital to specialise in caring for children. There she met Ian Hann, who was running the haemophilia centre, which had only about 40 patients.

“Most of those had severe haemophilia. Some many of them had HIV or hepatitis C. We had two children who had inhibitors who were an absolute nightmare.” This was in 1991, when there was virtually nothing with which to treat them. Even though prophylaxis was available, this generally meant taking about 500 units of factor VIII in a 40-50 ml syringe, too large for children with small hands to be able to press on the plunger. “Think about that now when you’re giving those 2ml injections, how much easier it is for children with haemophilia to self-treat.”

Along with Dr Hann, Kate started moving all of the GOS children from on demand treatment to prophylaxis. “As prophylaxis became available, we started out doing home therapy. And we used lots of port-a-caths so we could initiate high dose prophylaxis.” Gradually moving from plasma-derived products through from low purity to intermediate purity to high purity to recombinant products, the development by Novo Nordisk of NovoSeven proved a godsend for those two boys with inhibitors, and later on for more children with inhibitors and many with Glanzmann’s.

Dr Hann was very keen that research at GOS was not just done by him but by the whole of the team. His support meant GOS became a centre known for physio research and nursing research as well for clinical trials. “We were very involved in the PEDNET studies, I became a primary investigator, which for a nurse back in those days was amazing. That’s very much thanks to him and his support.”

Kate worked with Sylvia von Mackenson on the Haemo-QoL, a tool for measuring the impact of treatment beyond joint bleeds and trough levels, and undertook surveys looking at quality of life assessment in children with haemophilia.

Heeding the advice of her grandfather (“Kate, you’ve got two ears and one mouth. And that’s so that you listen twice as much as you talk”) Kate kept on listening to her patients. “What occurred to me when we were doing these quality of life assessments and the boys were all scoring really well, and were not bleeding and were out there playing sport was that they said, life is not great. It’s a bit miserable. I’m not as good at sport as I could be. The treatment is horrible. I don’t like having haemophilia.” And that led her to think about what is it like to be a boy growing up with haemophilia in the UK. It became a PhD project called “an exploration of the lived experience of boys with haemophilia.”

Kate found the children she engaged with to be really creative, taking photographs, drawing, telling their stories, writing their stories, and taking part in focus groups. and much of her research was co-designed with Charlie Collier, one of her patients. “Having somebody with haemophilia helping you to deliver and design research, I think is really important.” Together, they co-authored some of the papers that led ultimately to the award of her PhD.

Kate’s research didn’t stop there. As Director of Research at Haemnet, she has brought her “active listening” and patient-focused approach to designing studies looking at what it’s like to live with bleeding disorders and the impact of new treatments. “We are looking in particular at rare bleeding disorders at the moment. As a community we’ve done haemophilia but what have we done about Glanzmann’s or von Willebrand disease, or pain.

She has also been the driving force behind the development of The Journal of Haemophilia Practice as a vehicle to publish some of the papers that the more science-focused journals have traditionally shown little interest in publishing.

Kate says she is very proud of all of the things that she’s done, ‘but I haven’t done them on my own, so a massive thank you to every child with a bleeding disorder, for talking to me, to their parents, for putting up with me saying, please fill in another survey, to Ian Hann and the GOS and Haemnet teams and to the pharma industry for improving the treatment that we’re giving to people.”

And of course, with much more Haemnet research planned, she will go on using those two ears to listen to what people are saying and win over their hearts.

If you’re interested in undertaking some research to better understand the patient experience, get in touch for a chat with our legendary Director of Research and the Haemnet team – research@haemnet.com